Dave Darby, Co-founder of The Open Credit Network, reflects on money and capitalism after a year working on mutual credit.

In the summer of 2018 I went along to Open2018 to see Matthew Slater talk about how we might shake up the money system with a global Credit Commons. After his presentation, Matthew and I met with Oliver Sylvester-Bradley of the Open Co-op, who organised the event, and decided to build a mutual credit network for the UK.

We favoured co-operative ownership, with free / open source software that anyone could use to set up a local mutual credit network, and that could form the basis of a global system. We invited in Dil Green, my colleague at Lowimpact.org, some great volunteers and a top team of advisors, and the Open Credit Network was born.

Since then, I’ve been trying to get my head around the money system, and I want to summarise what I’ve discovered. If your new year’s resolution is to find out more about how the world is run, I’ve done some spade work for you. I’ve read:

- Money: the Unauthorised Biography, by Felix Martin

- Money: Understanding and Creating Alternatives to Legal Tender, by Tom Greco

- The End of Money and the Future of Civilisation, also by Tom Greco

- Matthew Slater’s Credit Commons White Paper

- The Politics of Money, by Frances Hutchinson, Mary Mellor & Wendy Olsen

- Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, by Douglas Rushkoff

- Debt: the First 5000 Years, by David Graeber

- Beggar Thy Neighbour, by Charles Geisst (also on the history of debt)

- The Ascent of Money, by Niall Ferguson (for a right-wing perspective)

- and I’m currently reading Glyn Davies’ 900-page epic, History of Money

… and a few that are more about wider solutions than just the money system:

- The Ecology of Freedom, by Murray Bookchin

- Parecon, by Michael Albert

- The Leaderless Revolution, by Carne Ross

- A New Politics from the Left, by Hilary Wainwright

- Markets not Capitalism, by Gary Chartier & Charles Johnson (for a different angle)

- The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich von Hayek (for a very different angle)

I think I’m beginning to get a handle on money, how it fits into modern capitalism, and what the alternatives to both are. Here are the four take-home messages I’m receiving:

- The state and the banks have a symbiotic relationship that controls the global economy in ways that are not well understood.

- The state is the junior partner in this relationship (in the West at least; the state is the dominant partner in China).

- Everyone can play in the global casino, but will be fleeced by the big players.

- A solution can only be reached by building community-embedded, decentralised alternatives that we own, and persuading people to move to them. Any other approach will be neutralised by the state-bank alliance.

1. The bank-state alliance

State tax receipts always lag behind state spending – and cutting spending or increasing taxes are always unpopular. Another source of funding is required, and that source is the banks. The state gives banks a licence to create money from nothing, as they make loans, with interest attached (see this video from Positive Money for an explanation).

In return, the banks commit to buy government bonds with this magic money, to keep the capitalist show afloat. Ordinary people ultimately pay for all this, via interest and taxation, and meanwhile, wealth is sucked out of our pockets and out of our communities, to concentrate in the banking sector and in tax havens, while national and global debt continues to balloon unsustainably.

Both those who self-identify as left or right see the state as a counterbalance to corporate power. In other words, they believe that if the state shrinks, corporate power will grow. The left have a problem with that and the right don’t (apart from some on the libertarian right), but I believe that they’re both wrong. Many on the left feel that the state is our friend, and will protect us from raw corporate power. However, the state is essentially a prop for the banks and corporations to maintain their dominance. The minimal social security that the state provides is a safety valve to prevent social unrest, so that the status quo can be maintained.

The right tends to believe that ‘dog eat dog’ is just the way the world is (as explained by George Lakoff), and so the top dogs deserve to be at the top. It doesn’t matter how they got there, they deserve respect – and anyone can get to the top if they work hard. For the right, this hierarchy is natural, and ensures stability and prosperity.

In my view, the state-corporate alliance means that shrinking the state will cause a similar shrinkage in the corporate sector. How well do you think corporations would compete with small businesses if they had to pay the same percentage of their revenue in tax, or there were no laws to protect their patents, or they could no longer get preferential treatment for government contracts, and ultimately, didn’t get bailed out if they fail? And how would banks fare without a state-granted monopoly on the issuance of legal tender?

However, the right only want to shrink the state selectively. Sure, they’d be happy shrinking the NHS or social services, but they’d want to keep a strong military, police force, courts, prisons and property laws – including intellectual property. (On the libertarian right, this is called ‘minarchy’ – i.e. keep the components of the state that are ostensibly for stability and security, but are also very much about protecting corporate profits and power).

Without a viable solution, left and right will continue to cancel each other out, bickering insignificantly, as the Titanic of humanity continues to sink.

2. The state is the junior partner (in the West at least)

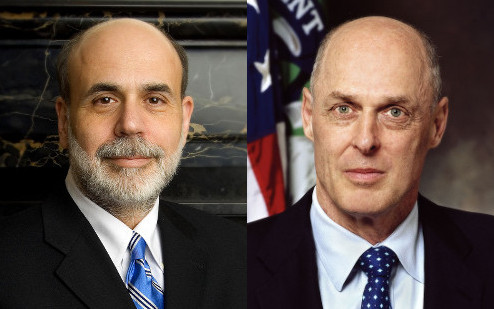

There was an event in the autumn of 2008 that illustrated this state-bank alliance very clearly, as well as the fact that the banking sector is the dominant partner in the alliance. Neither left nor right had any idea what to do about the financial crash of that year, and neither (of course) did the ‘Commander-in-Chief’, George W Bush. But two men understood very clearly what had to be done.

Representing the state side of the alliance, Henry (Hank) Paulson was the US Treasury Secretary (the equivalent of the Chancellor in the UK). Paulson was previously the CEO of Goldman Sachs, and was appointed as head of the US Treasury by Bush.

Representing the bank side of the alliance was Ben Bernanke, Chair of the Federal Reserve (the equivalent of the Bank of England in the UK). He was an economic advisor to Bush, and was appointed by him to head the Federal Reserve in 2006.

Ben Bernanke and Hank Paulson.

These two men, never having stood for election, and with absolutely no intention of ever doing so, were about to demonstrate their power. They discussed their plan privately, then presented it to Congress. Congress was to transfer $700 billion of taxpayers’ money (which would eventually run into the trillions) to them, with no strings attached, to use as they saw fit. There was no time to debate it – it had to be done quickly, if members of Congress didn’t want to go down in history as the people who broke America. There were appeals for the money not to be used for bankers’ bonuses, and that there should be stipulations that the kind of activities that led to the crash should not happen again – but these were refused. It was passed into law within 2 weeks. The money was used to bail out the banking sector – i.e. it was given to bankers.

It was the biggest transfer of wealth from ordinary people to an elite in history. Every other Western country was told to follow suit, and of course they did, with the exception of Iceland, who would have had to come up with an amount eleven times the size of their national economy to bail out their banks, such was the dominance of the finance sector in the Icelandic economy. The rest of the world had to rescue the Icelanders, who, to their credit, were the only nation to put any members of their bank-state alliance in jail.

3. We can all play the money game, but we’ll be fleeced

As technology has improved, investment houses have developed algorithms that can scan stock prices, and buy and sell much more efficiently than humans. What should have been obvious though (and probably was) is that the wealthier the financial institution, the more money they would be able to pay for the best programmers to develop more and more powerful algorithms on faster and faster computers, in a financial arms race. According to Douglas Rushkoff (Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, p. 180):

“Algorithms run on ultrafast computers connected as physically close to stock exchange computers as possible. This gives them a processing and latency advantage over their peers and any remaining human traders. A well-located algorithm can take action between the moment a more distant human or computer makes a trade and the moment that trade is fully executed. This is essentially ‘front-running’ other people’s purchases – buying the shares they intend to buy and then selling them to those same traders at a profit. Although it may cost the trader only a few pennies extra, those pennies add up when algorithms perform these routines millions of times a day, extracting real value from the market.”

… and …

“Algorithmic trading doesn’t happen on a laptop connected to the net by Wi-Fi. It requires the kind of hardware, connectivity and real-estate location that only the wealthiest, most established firms can afford. It may be disruptive to trading, but it only enhances the advantages of the traditional players – or at least the firms they worked for before they were replaced by machines.”

Many ordinary people (Americans especially) now play the stock market online, but are gently fleeced without knowing it by the world’s wealthiest financial institutions.

4. The community-based solution

So what’s the solution, when elections are about trying to make life more bearable on the Titanic, without actually noticing the impending doom, and rising up to overthrow the system is a dangerous pipe-dream, bearing in mind the power of the state-corporate military machine?

I believe that bringing people together in communities is they key. We can provide food, housing, energy, employment and the essentials of life together in our communities – whether those communities are geographical, sectoral or digital. These things are already happening, with sole traders, worker co-ops, housing co-ops, consumer co-ops, platform co-ops, land co-ops, community land trusts, community energy schemes, community-supported agriculture projects – plus ‘commons’ institutions such as Wikipedia, FOSS and Linux offering free alternatives to corporate products.

Mutual credit is the natural exchange system for this new kind of economy, and also, crucially, the only exchange system with the ability to ultimately challenge the dominance of the banks. Crypto has been used for speculation and as a store of value much more than as a means of exchange, and the local currencies popular in the last decade need to be purchased with, and are redeemable for, conventional money, tying them to the damaging system described above. However, they’ve demonstrated that alternatives are possible. Mutual credit gives us the means to exchange things with each other, using our own credit – a medium that can’t be sucked out of our communities.

I don’t believe that a community-based economy is about sacrifice. I think that it would improve life for almost everyone, making communities friendlier, safer and more interesting – replacing shelf-stacking, telesales and checkout jobs with craft production, renewables installation, smallholding, small manufacturing and independent shops and restaurants. Only corporate executives and major shareholders would lose out – but only if they don’t value stronger communities more than they value money (which I guess they don’t).

There are already numerous regulatory barriers to informal and local economic activities erected by the state (and we might anticipate more of these barriers while powerful corporations are partnering with the state to write the laws) – for example: extortionate licences for platform co-op alternatives to Uber; farm subsidies only for large holdings, so virtually no subsidy for land co-ops or CSA farms; regulation to prevent community energy schemes providing energy to their members, and that virtually bans onshore wind turbines; and in many cases, regulation to curb the excesses of industrial agriculture put small producers out of business because they can’t afford the stainless steel units that are needed to be able to sell their produce; and so on. Attempts to build a decentralised political economy have regularly been crushed by centralised power (the Diggers in the 17th century; the Paris Commune in the 19th century; Ukraine after WW1; the anarchists in Spain in the 1930s; the Ujamaa system in Tanzania in the 1970s and Rojava right now) – but the growth of the new, decentralised economy might (hopefully) be more difficult to stop in the age of the internet.

This article, by Open Credit Network co-founder Dil Green, is the best explanation I’ve come across of how a new, community-based economy could grow to transcend the current, centralised, bank-state alliance.

Conclusion

I don’t believe that a very high percentage of the population understands the nature of the state-bank alliance that dominates economic policy and pushes debt ever higher; or that economic power trumps political power in the West; or that more and more plucky amateurs playing the stock market from home strengthens the position of the largest financial institutions.

I don’t want you to take this as gospel however – I’m just repeating the claims of the authors mentioned above. But they are credible authors, and their claims deserve to be investigated. In any case, if you come across these claims from other sources, you won’t be shocked.

So what can you do to help build a new economy that is embedded in communities and that doesn’t strengthen the hand of the state-bank alliance? You can use Lowimpact.org to gain skills to do things for yourself, and perhaps to switch to a career that’s more compatible with this new economy; and you can visit Noncorporate.org to find ways to purchase the essentials of life from already-existing new economy institutions.

And very importantly, to challenge the dominance of the corporate banks directly, you can help erode their base by registering your business in the Open Credit Network directory, and then upgrading to a trading member, to begin to trade with other businesses in mutual credit, an exchange medium rather than a store of value, that can’t be sucked from our communities to accumulate globally in the hands of a tiny elite of bankers. [A word about elites: this is not about individuals, families or particular companies, who could not be removed without others rushing to fill the vacuum that would be created. The problem is a system that generates elites – which, after thousands of years of bloody empires, we still have.]

The Open Credit Network is the only organisation in the world, as far as we know, that is building a mutual credit system with democratic ownership and software that will be free for any incipient group to use, to build a local network that can plug into a global trading system – a Credit Commons. We’re recruiting small businesses and sole traders at the moment, and we’re working on ways to include individuals, either as part of a club or co-op, or via the companies that they work for. But it’s important to base the network on businesses – to build a new economy, rather than a network of hobbyists.

[NB: I haven’t even mentioned the role of the petrodollar as global reserve currency, or what will happen when China takes over (same destructive game, different centre of power), as that’s another story, and this article is already way too long.]

About the author

About the author

Dave Darby lived at Redfield community from 1996 to 2009. Working on development projects in Romania, he realised they saw Western countries as role models, so decided to try to bring about change in the UK instead. He founded Lowimpact.org in 2001, spent 3 years on the board of the Ecological Land Co-op and was a founder of NonCorporate.org and the Open Credit Network.